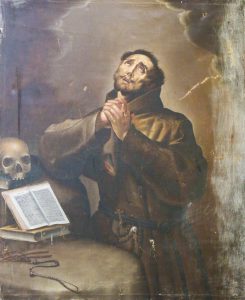

A depiction of the Final Judgment by Leandro dal Ponte.

By Casey Bassett

Imagine jumping into a vehicle, knowing you had to be somewhere but not knowing anything about the destination or how to get there. And, as you start driving, you know nothing about the rules of the road. It’s almost certain the trip will not go well, and even if you somehow reach the destination, there are bound to be some major impediments along the way.

This scenario sounds absurd, but it’s the state in which many of us find ourselves on the journey through life.

The world tends to swallow many of us up in distractions and pleasures (such as the endless scrolling through mindless chatter on our smartphones) that can give us a feeling that things will go on forever. The proposition that we could and, in fact, should ponder our final destination—death—in a prayerful and enriching way tends to be an altogether repugnant idea in our modern culture.

“If I’m going somewhere, I’m starting with a destination in mind,” says Dr. Chris Burgwald, director of discipleship formation for the diocese. “Begin with the end in mind.”

Wisdom of the Church

Throughout the ages, the Church has understood the importance of realizing and prayerfully pondering our own mortality. While the Church asks us in November to turn our focus to the faithful departed gone before us, Advent is a time to look ahead to our own end and the second coming of Christ. The “Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year and the Calendar” (39) states:

“Advent has a twofold character, for it is a time of preparation for the Solemnities of Christmas … and likewise a time when, by remembrance of this, minds and hearts are led to look forward to Christ’s Second Coming at the end of time.”

Lending our hearts and minds toward our death and the end times can seem intimidating and far removed from what we might call the “Christmas spirit.” But in her wisdom, the Church understands that a soul knowledgeable and prepared for the end will be able to reach a more profound level of joy when celebrating Christ’s birth on Christmas Day.

Moreover, Advent is the beginning of the liturgical year, the start of our year-long liturgical journey through the many seasons and solemnities of the Church. Refocusing and reflecting on our final destination can induce us to go deeper into our faith, to learn the rules of the road so-to-speak, which will guide us in our Christian lives throughout the next year.

How, then, do we perform this reflection? A fruitful reflection starts with a basic understanding of our destination, which can be encapsulated in what are known as the four last things: death, judgment, heaven and hell.

The four last things

“I am my body and soul together, that’s what makes me, me,” said Dr. Burgwald. “From a theological sense, death is the separation of the soul from the body. This is why death is, in probably not the obvious way that most people think about it, a horrible thing. Because the body and soul are supposed to stay together, they’re not supposed to be torn asunder. But because of sin, they separate. This is a fruit of Original Sin.”

God did not intend for our souls to be split from our bodies. Rather, it was our choice to try to usurp him through Original Sin that led God to inflict the just punishment of death. Yet, in his divine providence and mercy, God turned the punishment of death from a finality to an opportunity.

“Death is not the ultimate end,” says Dr. Burgwald. “It’s the doorway to the next state of our existence.”

Like waking up from a dream where reality was clouded, when our soul steps through this doorway, we will find a level of clarity that makes our earthly life seem cloudy and confusing in comparison. We will instantly be keenly aware of God’s mercy and justice as well as our own sins and the harm they caused to our relationship with God.

It is at this moment that we will face our particular (or personal) judgment before God. The Blessed Mother, many saints (especially the ones from whom we sought intercession and assistance during our life), our guardian angel and even, perhaps, our faithful departed relatives will surround us and advocate on our behalf.

Christ was clear on the dichotomy that exists in this judgment. Those who walk in light, cooperating with God’s divine will in their lives, have a joyous hope of joining the saints in heaven. Those who continually follow their own will, forsaking God’s will and ultimately the grace of repentance, risk eternal separation from God in hell.

“Nobody will be surprised at their particular judgment if they are going to hell. Hell is the consequence of me saying no to God and God will respect my freedom,” said Dr. Burgwald.

Since the veil has been pulled back, this soul will be keenly aware of the justness of God’s judgment, and it will willingly flee his presence, a presence that becomes unbearable in the clarity of that soul’s sins.

Until the general judgment, our soul will exist without our bodies in one of three states: a state of union with God (heaven), a state of complete separation from God (hell) or a state of purification in preparation for heaven (purgatory).

“At the end of time, there will be the general or universal judgment when every single person who has ever lived will be reunited body and soul, and we will together, as humanity, stand

before the judgment seat of God, and we will see everything we have ever done, good and bad,” Dr. Burgwald said. “The presumption being that we will see everything, good and bad, that everyone else has done.”

While the effects of our sins on our personal relationship with God were made visible to us at the time of our particular judgment, the whole effect of our good and bad works on everyone else throughout time won’t be revealed until this final judgment. As Dr. Burgwald mentioned, we see the works of everyone else, and in this, the whole of God’s plans in creation will be revealed to us in its magnificent glory.

As theologically ponderous as they can be, having at least a basic understanding of these last four things assists us in being prepared for them. Once we can grasp the basics, this preparation is primarily developed through prayer and contemplation. There are many ways via the saints and traditions of the Church that these seemingly somber and remote realities can become beautiful and enriching parts of our faith life.

The temporal and eternal rest

In her prayer, the Church has always held nighttime and sleep as a symbol of our death and a reminder of its inevitability. In the Liturgy of the Hours, the night prayer for each day

contains the response, “Into your hands, Lord, I commend my spirit,” along with the concluding blessing, “May the all-powerful Lord grant us a restful night and a peaceful death.”

As the light of day fades and we, weary of our toils, yearn for the rest of our beds, our night prayer can be a time to reflect on our day as if it was our whole life. With sleep as our symbolic final end and the day as our entire life, we can ask our Lord to confer the grace upon us to see our actions, exterior and interior, throughout the day in light of how he would judge them.

Just as we hope in the bright dawn of our salvation, we also hope in the dawn of a new day where we will be reinvigorated from restful sleep. While the eternity of our death and judgment is final, a new day in this life is an opportunity, born out of God’s mercy, to live in more perfect cooperation with God’s will. Our rising in the morning and going to bed at night, each day is a practice session for our ultimate end: death and judgment.

Remember your death

Many saints took this symbolism into their work during the day.

“The saints adhered to the practice of memento mori, the Latin phrase for ‘remember that you must die,’” said Monsignor Charles Mangan, a priest of the diocese whose knowledge of the saints is well-known. “St. Jerome had a human skull on his desk, while St. Francis of Assisi carried the same with him. St. Benedict urged his monks in his ‘Rule’ to ‘keep death daily’ before their eyes.”

Having a skull at eating tables or desks in monasteries was widely practiced by many religious communities. The ultimate purpose of this was to remind the individual, awake among worldly things, that all with which they were surrounded was fleeting and temporary. This had the effect of sobering the individual from getting overly attached to daily pleasures, including food and drink.

“In our work life, we realize that while any material treasures we obtain will pass away, our efforts to cooperate with God in the building up of his kingdom here on earth will last after our departure,” Monsignor Mangan said.

A form of this practice was adopted by laity who worked extremely dangerous jobs. Before leaving for work, they would place a crucifix on their pillow both for protection during the day and as a reminder of the proximity of death during their daily activities. This tradition has, for the most part, been forgotten, but restoring it during the Advent season, even if your job isn’t particularly dangerous, can be a prayerful way to remember your final destination.

Heaven on earth

Finally, our day or week is hopefully crowned with our participation at Mass. This sacrifice of the Mass in itself is a reminder that what our material senses perceive is the smallest and dimmest piece of reality.

“At Mass itself, the veil between heaven and earth, between history and eternity is removed,” Dr. Burgwald says. “When Mass begins, we enter into the heavenly throne room.”

Until our death, at no point are we closer to heaven than at the Mass. During the consecration, surrounded by throngs of unseen angels and the faithful departed, our Lord becomes truly present in the sacrament of the Eucharist. So too, at our death, surrounded by those same angels and saints, our Lord will become present to us in his unimaginable beauty and splendor with the final veil of reality pulled back.

In her Advent liturgies, the Church takes up a quiet, expectant tone. Enter into that quietness at Mass and meditate on your proximity to God. Consider lingering in his throne room after Mass and pray that just as you dared to humbly approach him in the Eucharist, so, too, he may grant you the grace to approach him at the hour of your death, full of humble repentance and hopeful confidence.

“In our prayer, we recognize that our true home is heaven, and we pray to God for the grace of final perseverance, meaning that we persevere in the ‘state of grace’ (meaning without mortal sin) until God calls us. We invoke Our Lady for the virtue of humility and St. Joseph for the grace of a happy death,” Monsignor Mangan said.

Joy of Christmas

In all these small ways of prayer and meditation, the hope is that the reminder of our destination will guide our journey in the Christian life throughout the new liturgical year. This reminder can serve to lessen our attachment to material goods, sober our passions and induce us into virtue, especially charity.

When we realize our end, we realize the time to be kind and generous to one another in this life is very short. How much deeper would the notable generosity of man during Christmastide be if he remembered the shortness of his days?

An Advent full of prayerful reflection, contemplation and preparation will allow you to reach more profound depths of peace and love on Christmas day, for you will know the material things of this world are enjoyed most perfectly when viewed through the lens of temporality.

You will more perfectly understand that the permanence and depth of the joy of Christmas day comes from what is immaterial, most notably generosity born out of love. And in the new year, you will be ready for the graces God has prepared to pour out upon you, inviting you deeper into your faith and closer to your last and eternal stop on this brief journey of life.